Iron Shot

Your basic cannonball: a single sphere of iron, shot from a cannon to smash into the enemy ship.

In naval battles, very flat trajectories were preferred to maximize the chances of hitting the target. At close range, double-shotting was sometimes employed. Two balls in one cannon meant double the damage at the cost of a massive reduction in range and accuracy.

These projectiles weren't a snug fit: cannon balls and cannon bores both had irregularities from limitations in their manufacturing. So balls basically bounced along the bore when fired.

Stone Shot

An early kind of "explosive" ammunition made of stone cut into spheres. It would shatter on impact, leaving jagged holes in the hull and injuring anyone nearby.

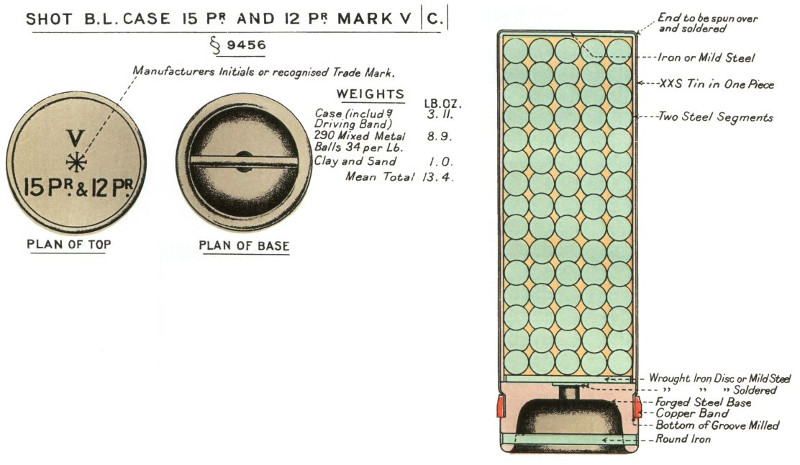

Canister Shot

A metal cylinder filled with lead or iron balls. The case would disintegrate immediately after firing, spraying shards and projectiles in a conical pattern, like a giant shotgun. This was extremely effective against enemy crew, but only at close range.

If proper ammunition was scarce, canister shot was sometimes made of random scrap metal, rocks, and any other hard things that could be found lying around. This was referred to as scrapshot or langrage.

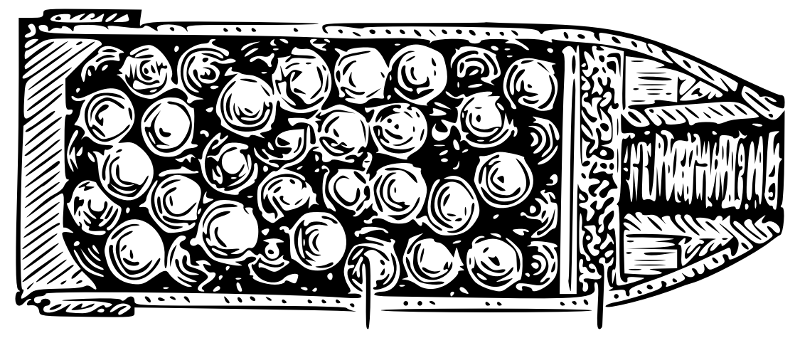

Grapeshot

So called for its resemblance to a cluster of grapes, this munition was similar to canister shot, consisting of a number of smaller balls held in a canvas bag. It, too, had a shotgun-like anti-infantry effect, but the balls used were generally fewer and larger, which made them more effective against masts, sails and rigging.

As with iron shot, canister- and grapeshot would sometimes be double-shotted, to devastating effect. To avoid bursting the gun when firing, the amount of powder used had to be reduced, which made double-shotting only effective at very close ranges.

Chain Shot

A specialized form of ammunition, chain shot consisted of two iron weights linked by a chain. When fired, the chain would extend and sweep through the target ship, taking down masts and rigging and cutting the occasional crew member in half. This allowed ships to slow down or immobilize their enemies, to be able to out-manoeuvre them, or as a prelude to boarding.

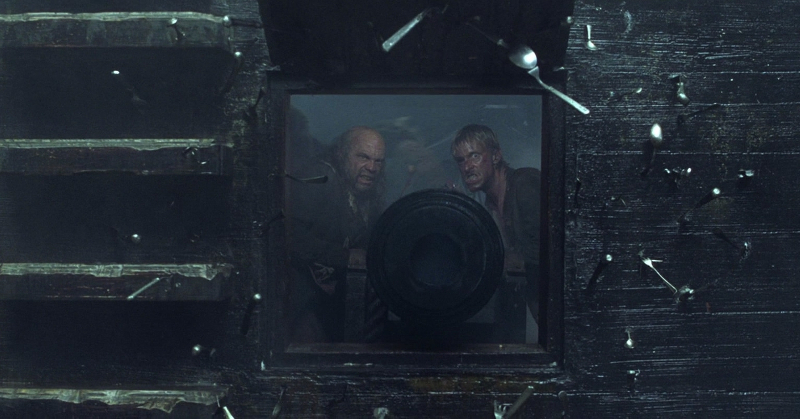

Scattershot

An improvised form of grapeshot made of whatever came to hand - nails, glass shards, rocks - anything hard enough to cause some damage. This only worked at close range, and badly at that, as the ballistics of these improvised projectiles was very random.

So yes, that scene from Pirates of the Caribbean was less absurd than you might have thought.

Carcass

But why only rip your enemy apart when you could also set them on fire and poison them? A carcass was an iron frame covered in cloth, or a metal shell, filled with flammable and noxious substances like pitch, sulfur and turpentine. This projectile would be aimed at the deck of the enemy ship. Ignited by the cannon blast, it would smash open on impact and set fire to its surroundings while releasing poisonous fumes - an early form of chemical warfare.

Carcasses were especially popular with bomb vessels, ships built for bombarding stationary land targets using mortars. Which brings us to a fun detail - the reason why Mount Erebus and Mount Terror in Antarctica have such scary sounding names. They were named after the two ships that comprised James Ross' Antarctic expedition. And why did the ships have such scary names? Because they were formerly bomb vessels! They were chosen for this expedition because they were of especially rugged construction so they could withstand the recoil of their mortars. Due to their focus on destructive power alone, bomb vessels commonly had fiery, nasty names, such as Serpent, Furnace or Dreadful.

Heated Shot

Another way to set your enemy on fire was to take an ordinary iron cannonball, make it red-hot in a furnace, and then fire it at the enemy. There were a number of problems with this idea, though: Imagine you're in a sea battle. The ship is pitching back and forth. You are carrying a red-hot iron ball in an iron container. You must deliver said ball to the mouth of a loaded cannon, without dropping it, without accidentally igniting any wood, cloth, rope, or stray powder.

Unsurprisingly, these projectiles were only really used by land-based forts.

Shrapnel Shells

Canister shot was great for tearing apart enemy crew, but it was short-range. What if you wanted to cause mayhem from a greater distance? Enter Major General Henry Shrapnel of the Royal Artillery, who in 1784 developed a kind of canister shot with a sturdier casing and a timed explosive charge. If the fuze was timed just right, the shot would explode just above the heads of the enemy crew, turning them into mince-meat. If the fuse was long, it would still explode after impact. If it was way short, well...

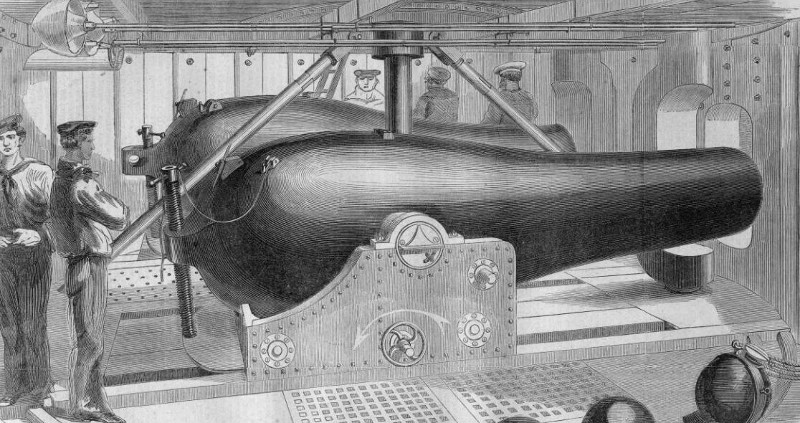

Explosive Shells

Explosive projectiles had long been a staple of land-based artillery, but it took until the 1840s for sea-based explosive shells to be deployed. The reason for this was that sea-based guns had to be far more powerful to allow for the kind of flat trajectories employed in naval battles. This kind of gun would ignite an explosive shell while it was still in the barrel!

Land-based artillery on the other hand used comparatively leisurely parabolic trajectories and could be a lot "gentler" with its shells. But by the 1890s, technology had advanced enough that ship-based guns could fire high explosive shells extremely effective against older wooden-hulled ships.

Armour-piercing Shells

With explosive shells making wooden ships rapidly obsolete, iron-hulled ships came to the fore. Ironclads were virtually impervious to conventional shot, as was demonstrated during the famous Battle of Ironclads during the American Civil War.

To get around this, new projectiles shaped like giant bullets were cast, their tips hardened. These worked against wrought iron armour, but armour development progressed as well, resulting in steel and composite armour. This in turn required steel shot and more powerful propellant, and the race between armourers and gun-makers was on, all in pursuit of naval superiority...