But the impact factor is not the whole story: there is a lot of junk science out there, and some of it with a great number of citations. If a paper makes some exciting claim, it may get a lot of attention, but it may also turn out that this exciting claim was simply wrong.

One example is a paper called "Positive Affect and the Complex Dynamics of Human Flourishing" whose findings have been cited 350 times and are part of the bedrock of the psychology of "positivity". Unfortunately, it's also pretty much garbage. The authors attempt to calculate a required ratio between positive and negative thoughts by using a formula borrowed from fluid dynamics, equating the physical flow of liquids with the "emotional flow" of human beings, and getting a ratio of precisely 2.9013 positive to one negative emotions.

This paper is, frankly, an embarrassment, and anything but a good foundation for future research. But it's so commonly cited that many writers don't give it a second thought.

Beyond junk like that, there are also papers that have simply been retracted, or shown to be incorrect by subsequent research. Other papers, while there is nothing visibly wrong with them, are under a cloud because their author has been caught serially faking data - as happened in the case of Yoshitaka Fujii, a prominent anesthesiology researcher. We know for sure that he faked data in 172 papers, but other papers may have been contaminated too.

Finally, there are also papers that have been published by journals with less than stringent controls. This can be journals such as Medical Hypotheses, which for all the flak it gets, is explicit about its aim to set the bar low and accept out-there submissions - but also journals like the "Australasian Journal of Bone and Joint Medicine", which was created out of whole cloth by Elsevier to place favorable results about products by the pharmaceutical giant Merck.

All of this means that beyond the impact factor, we may also want a "bad science contamination" factor for papers. A high contamination factor doesn't mean that the paper itself is bad, only that its associations are less than pristine.

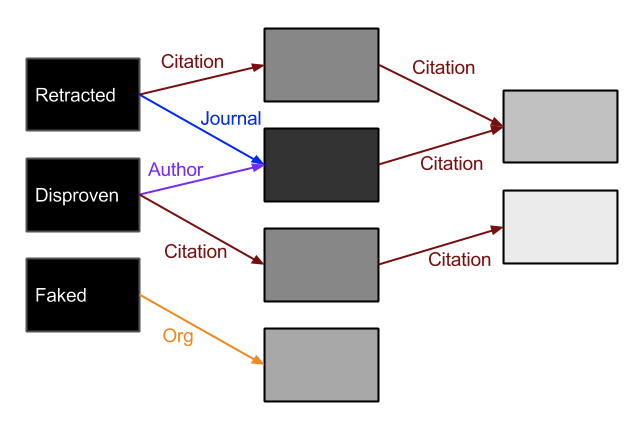

The way this works is something like the reverse of the impact factor. Given the set of all papers published, we identify a subset of "bad papers": retracted, disproven, garbage papers. We set their badness factor to 1. ("Wrong")

We can tune the transmission factors as well: having the same author may be considered worse than turning up in the same publication.

In the end, all papers have some nonzero badness score, but you can see the dubious areas. Maybe a paper looks fine by itself, but cites a whole bunch of discredited papers and lists as its co-author someone associated with a notoriously corrupt research institution. Again, that doesn't mean there's anything wrong with it, but the higher the badness factor, the closer a look you may want to take before taking it at face value.

Ideally, such a system would stop people from citing papers known to be garbage out of sheer habit. It would also discourage the tendency to cram in as many citations as possible, relevant or not. Instead, you would want to focus on a clean, well-curated group of papers that you really do have to link to.

Unfortunately, this system also has a lot of potential for things going wrong: for starters, papers and individuals may end up with a high badness score out of no fault of their own. Also, if you measure something, it changes: creating an incentive to have a low badness score will inevitably cause people to game the system. And it may actively discourage scientific collaboration, as a single ill-chosen co-author might contaminate your work permanently.

This means that as soon as people take this measure seriously, its usefulness may degrade, which makes it more of a project to make a point than a tool for serious use. Still, it would be an interesting project to take on - if you're interested and want to collaborate, get in touch. I can do the coding if you can navigate the papers and scientific culture.