David Stark / Zarkonnen: gameMusings

- A Typology of Building Game Players

I've been thinking about games where you build stuff again. This is both because of the ongoing popularity of colony builder games such as Rimworld and Dwarf Fortress and The Wandering Village, and also because I'm embarking on another community-driven balancing round for Airships: Conquer the Skies, my own game.

I've come up with a typology of players for the sorts of games where you build things, especially strategy games. It also applies to games like Minecraft. This is probably not especially novel, but I wanted to get it down for my own reference, if nothing else.

- My Problems with City Builders

So currently city builders (base builders, colony builders, whatever) are a very popular game genre, and so it would arguably make sense for me to get in on that and make one too. After all, I already made an airship builder, so I have plenty of experience making games where you place structures and then little people run around. Except, unfortunately, I find myself pretty bored by the genre. I've played a fair amount of SimCity, Dwarf Fortress and RimWorld, and now I feel I've kind of... seen it when it comes to the genre.

But I think I also have Problems with the way these games work, which I will now try to explain.

- Armageddon Empires vs Old World

I mentioned on Twitter that I wanted to write a post comparing Armageddon Empires, a 2007 post-apocalyptic strategy game, with Old World, a freshly released historical strategy game. I bought Old World (OW), tried to play it, and found myself pretty bored, and returned to Armageddon Empires (AE). Why?

Actually writing this post has been a bit of a mess, because I'm trying to extract some game design thoughts from what's ultimately a subjective experience.

- A lost decade of Swiss games?

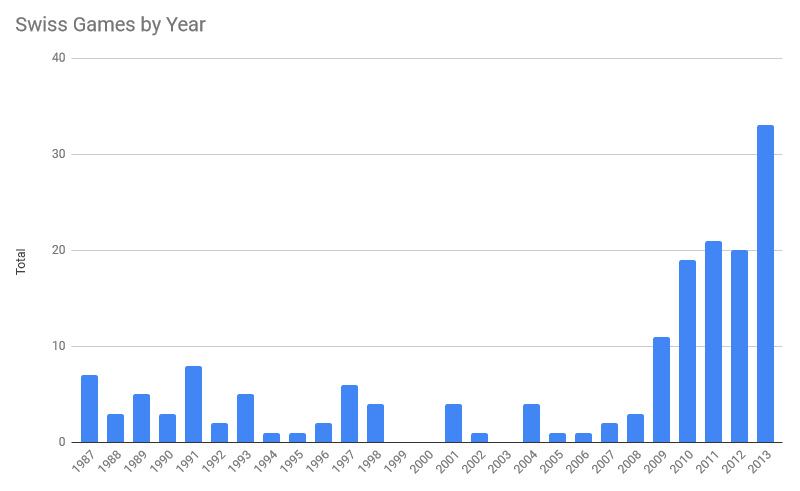

I've been contributing to compiling a complete list of Swiss games for a few years. It was started by David Javet, and consists of a Google sheet that aims to collect all computer games ever made in Switzerland. We currently have 458 entries going back to 1987.

But there's a weird hole in our data roughly spanning the decade of 1999-2008. In that decade, we only know of 16 games that were released. In the decade before that, 1989-1998, we know of 37 games. We have zero games recorded for the years 1999, 2000, and 2003. And then from 2009 onwards there's a huge increase in games that lasts until the present day.

Why?

- Block Size in Roguelikes

How big is a tile in a roguelike or similar game? What shape does it have?

I've been playing (and modding) a lot of Caves of Qud, so this is something I'm thinking about again. I'd love to see or make a roguelike where the levels are truly three-dimensional rather than 2D levels connected by staircases. Qud has some nods to three-dimensionality. Brogue has some more. Dwarf Fortress is 3D except that dwarves still don't understand about things like, for example, rooms that are taller than one floor.

So let's define the size and shape of these tiles.

- Caves of Qud, Dying, Setpiece Battles

I haven't done much blogging on here, mostly because of the self-reinforcing thing that if you haven't written anything for a while, the next thing you write had better be good - which of course means it dies as a draft, or in my head. So I'm going to intentionally lower the bar quite a lot and write down my thoughts.

My friend David uses a notebook blog for this, but I really don't want to complicate my web presence further, so it's going here.

I've been playing Caves of Qud a lot lately. It's been on my radar for a long time, but I only got it like a week ago. By and large, I'm really enjoying it. I never got very far into Nethack because it's a thematic mess where the devs went "what if we added ninjas/sokoban/cameras?" And other roguelikes are very generic fantasy paste.

Qud is both well-polished and has a coherent but weird and fun world. There's plenty of interactions and things to discover, and I'm getting better at it. I survived to level 19 in the latest playthrough!

As always, when I play a game, I'm thinking about what I'd change and improve:

- Quick Chimera Squad Thoughts

I just finished playing through Chimera Squad, the spontaneously appeared XCOM spinoff, on Normal/Iron Man. It's... an OK game. The writing is uneven: some of the banter is cringeworthy and your opponents are a bit uninspired. But I love the food ads on the radio.

They're also clearly trying out some new things, which is easier in a spinoff:

- Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri

I'm back playing Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri. I play a lot of strategy games, but this is the one I've been in love with the longest, despite its flaws.

It's now more than 20 years on, and kind of an abandoned evolutionary side-branch of the Civilization series. The more recent Civ-in-space, Civ:BE, was explicitly not a remake of SMAC. This was probably wise in that any attempt to directly improve upon a cult game would fall short. The problem isn't the game design, the problem is that the game can't make you feel like you're twenty years younger.

- Beyond Earth vs Alpha Centauri

This is now an incredibly cold take, but I finally wanted to write down my thoughts on Civilization: Beyond Earth (BE), and how it compares to Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri (SMAC), which is sort of its predecessor.

- The Transmission

This is my Global Game Jam 2018 entry on the theme "transmission". It's a short experimental piece of interactive fiction, where I tried to do A Thing with stories.

- Free player movement and static worlds

A game can either have an open world where the player can move freely, or a world that changes as the plot advances. If it has both, the player will miss out on most of the game's content. There are some approaches to deal with this, though...

So I've been thinking about the Skyrim Problem in RPGs.

In Skyrim, pretty much the first thing you find out is that big scary dragons have returned. And the main plot is about the return of these dragons. But there's also hundreds of side-quests you can do at your leisure. Indeed, once I stumbled into the nearest village after my dragon encounter, the first things that happened to me were a quest to deliver a ring, and a nice man who wanted to teach me all about smithing daggers.

But think about your character: would they at this point care about rings or taking up a career in smithing? Might not the whole dragon thing weigh a bit more heavily on their mind?

And indeed, you can play Skyrim like this, actually taking the dragon threat seriously, moving to warn and defend people as quickly as possible. This will also mean you skip most of the game. But you can also do all the side quests, and the dragons will wait politely as you learn how to make daggers or fix people's love lives, only arriving at the maximally plot-convenient time once you decide to take back up the main quest.

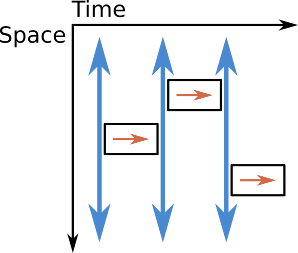

A diagram of how player movement and world time works in Skyrim. The player (blue) is able to freely move in space, but time is essentially frozen, until they go to a particular place, at which point time advances (red).

Now, some people don't mind this contradiction, but for me and a lot of others, it destroys my suspension of disbelief. It's a role-playing game, yet it wants me to play the role of a weird, endlessly distractable person whose dawdling somehow never matters.

Not all story-driven games are like this, though. Here are three ways to get around this:

- I have some pretty strong evidence that the Steam keys from the defunct IndieGameStand are being re-sold.

tl;dr: Developers, revoke the Steam keys you supplied to Indie Game Stand!

I'm the developer of a game called Airships: Conquer the Skies. It can be bought through a bunch of platforms, including Steam, and, until it shut down earlier this year, Indie Game Stand.

- Magic from Bargains

This post was originally published in 2013, on the previous incarnation of this website.

I just read a pretty neat article that argues for more interesting forms of magic in computer games. One idea I really like (because I'm horrible) is having to pay a permanent price for each spell cast. (The spells, in exchange, being very powerful and useful.)

- Grids in Games: Scale and Shape

I've been thinking about the different kinds of grids of tiles and blocks used in games, which come in a variety of scales and shapes.

- Voyageur, analysing a disappointment

I just bought and played Voyageur, a science fiction story game for mobile. It's one of the games supported through Failbetter's Fundbetter programme, and since I'm mildly obsessed with Sunless Sea, I thought I'd give it a try. I was largely disappointed, though.

I won't bore you with explaining how my own unreleased SF story game would be totally superior. You've read it here before, and comparing a real and finished game with a set of ideas is hardly fair. Instead, let's dig into what makes Voyageur unsatisfying.

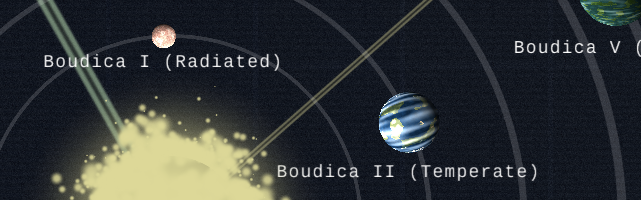

- Space Exploration: Serpens Sector - Notes on an eventual resurrection

I've been ill over the last few days, probably as an inevitable consequence of doing so many events in January. So I've been playing a fair amount of Sunless Sea, a great game if you're ill, because it's quite soothing in a "dark sea filled with monsters" kind of way.

And as always when I play Sunless Sea, my thoughts turn back to Space Exploration: Serpens Sector, my old game project that got backburnered hard when Airships: Conquer the Skies took off. The two games are in the same "go from port to port in your ship and do stuff" genre, after all.

- Space 4X is stuck in a rut

The last few years have seen a number of games attempting to reinvigorate the Space 4X game. They have all been disappointments. The trouble is that Master of Orion II still looms large. New games not only have to compete against it on their own merits. They have to be both better than MoO2 and at the same time deliver the exact same happy experience as remembered through a decades-old haze of nostalgia.

Space 4X games are stuck in a rut. Much as what used to be the case with Tolkien and Fantasy, or D&D and roleplaying, a single work looms large, and all other works have to define themselves in relation to it, either subverting or surpassing it, but always remaining deeply constrained by their genre.

- Drinking from the firehose

Short version: For one day, on Thursday, 23. June, I will buy and play every single game released on Steam that day. I will stream myself playing. I will play each game for twenty minutes, and at the end of that time, I will render one of two verdicts: "keep" or "refund".

There are so many games being released every day that it's become pretty much impossible to keep track of them all. On the iOS app store, there's now something like 500 new games every day. Almost all of those will sink without a trace, unnoticed and unplayed.

On PC, things are not (yet?) that extreme. About 20 new games appear on Steam every day. But it's still too many for any one person to keep track of, enough so that perfectly good games might get lost because of chance.

- Game ideas are plentiful and oft-repeated

I just came across the Kickstarter for Potions: A Curious Tale, a fantasy game with an emphasis on creative problem solving and experimenting with potion crafting. So pretty much this concept I wrote about nearly three years ago.

My point here is not that I think they "stole my idea". It is twofold: Potions: A Curious Tale looks like a cool game you might want to back and this is a great example of just how little a raw idea means in game development.

- Optimizing for boredom, why I stopped playing FTL, and Airships has no precise targeting

A while ago I listened to a podcast interview with one of the developers of Don't Starve. They were discussing the design of the Science Machine, the building that lets you discover new crafting recipes.

- Whatever happened to Space Exploration: Serpens Sector?

If you've been following me for a long time, you know that before Airships, I was working on another project called Space Exploration: Serpens Sector. It was a space RPG that started out as a clone of the original Strange Adventures in Infinite Space, and ended up being something like Sunless Sea in space with less florid writing and a bigger focus on crew management.

- Reverse Diablo

Be warned, this is a tasteless idea, but still kind of entertaining, which is why I wrote it up. Diablo in reverse: an action-RPG where you take on heaven, working your way through orphanages and monasteries, smashing through the pearly gates to take on the angelic host... and kill god.

- At The Gates: Roadmaps and Sacrifices

At The Gates is an under-development 4X game by Jon Shafer, a game designer formerly of Firaxis Games. In the game, you play as a barbarian tribe in the twilight days of the Roman empire. It got kickstarted back in early 2013 and has been making its way through the tortuous process of development ever since. I actually found out about it too late to join the Kickstarter, but I've been following its development nevertheless.

In his most recent update, Shafer sets out a roadmap for completing development of the game.

- Are small games viable?

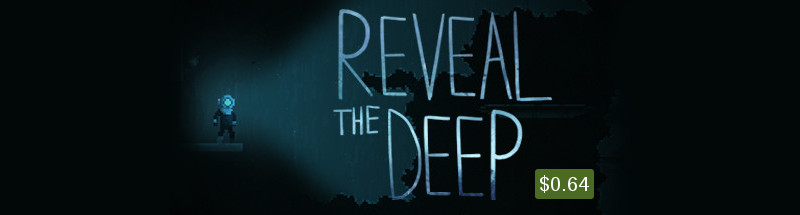

I'm not sure where I first saw Reveal the Deep. I thought it was on JGO, but I can't find any trace of it now. So I was vaguely aware of it when it popped up on the Steam new releases page, with a price of $1, launch-discounted down to 64 cents. And I was worried that the developers had so little faith in their game to release it for next to no money. Then I bought it because it looked vaguely interesting.

Turns out I wasn't the only one. A week ago, the developers posted a short postmortem on r/gamedev. The game made it into the "popular new releases" list for two days, and according to Steam Spy, has been bought about 36000 times! (The the devs confirm this is a roughly accurate number.)

Now I don't know how much you get to keep from a $0.64 Steam game. I'd guess it's somewhere between 50 and 70 percent, which means that the game netted somewhere between $11000 and $16000. Not a bad haul for what is a fairly simple, if well-executed game.

The question that arises from this for me as a game dev: Are small, cheap games viable on Steam?

- Urgency and suspension of disbelief in RPGs

I never finish role-playing games. A few hours in, I reach a point where I get overwhelmed by side-quests and options. My suspension of disbelief breaks down as it becomes clear just how much the world revolves around me: I can start a quest, wander off for three months, and when I'm back, everyone involved is still in the same place, patiently waiting for me to pick things back up. The main plot often claims to be urgent, and that is simply a lie: I can take all the time I like. The more I do, the more fake everything feels.